San Antonio rock quarries reborn as zoo, Alamo Stadium, other recreational sites

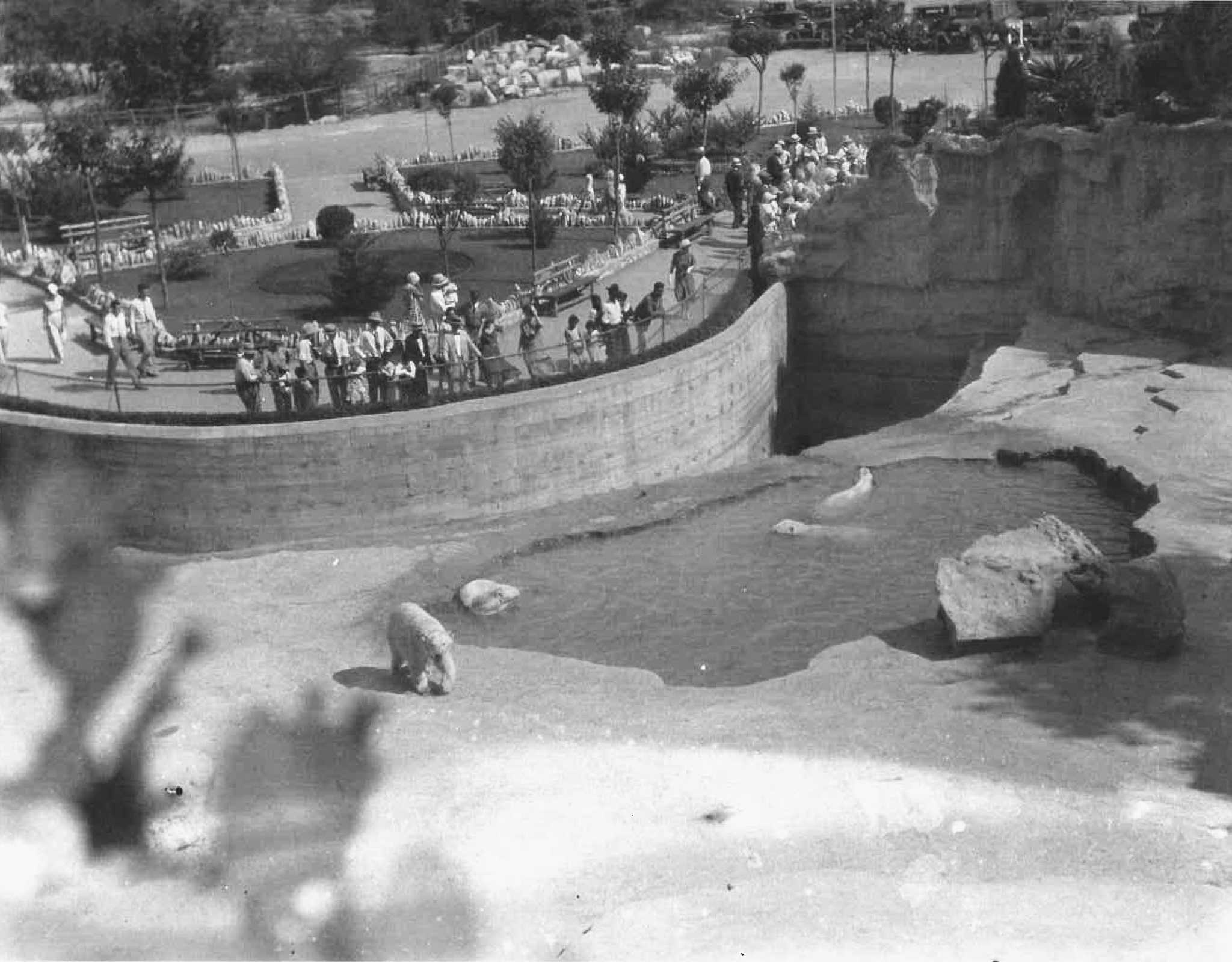

Reader’s grandfather was one of the workers who helped transform one of the sites into... This article looks at the history of San Antonio rock quarries that were once known as the Rock Quarry, or La Piedreda, and how they were once leased by the Alamo Cement Co. to the first manufacturer of Portland cement west of the Mississippi River. It also looks at how Refugio Lopez, the great-grandfather of the quarry's namesake, worked at removing stone from the Brackenridge Park quarry and building the San Antonio Zoo animal pits, as well as Alamo Stadium. The article also discusses the St. Louis Zoo's cost-effective enclosure design, which allowed animals to move around freely in more natural-seeming surroundings while separated from human onlookers by smooth walls, moats and elevated walkways for viewing.

Published : 2 years ago by Paula Allen, Guest columnist in

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

According to my mother, my great-grandfather, Refugio Lopez, worked at removing stone from the Brackenridge Park quarry, and worked in building the San Antonio Zoo animal pits, as well as Alamo Stadium. Could you provide more history/information about this?

Also, I grew up off North St. Mary’s Street and remember that the area by Brackenridge Park was called the Rock Quarry, or La Piedreda, as it was known to the Mexican Americans living in the neighborhood. When Alamo Stadium received a face-lift a few years ago, I was taken aback when Express-News articles referred to it as the “Rock Pile.” Where did that name come from?

Your grandfather, who lived from 1867 to 1941, might have worked in that quarry at several stages of his life, as the area progressed through different stages of its own. From 1880 to 1908, it was leased by the Alamo Cement Co., the first manufacturer of Portland cement west of the Mississippi River. (Portland cement uses a mixture of ground limestone and other materials fired in a kiln and ground again to make an exceptionally strong type of cement for concrete, known as “artificial stone.”)

MORE ON QUARRY: Smokestacks at Alamo Quarry designed in early 1900s

Once this original quarry was played out, with high-quality stone harder to excavate, the company, renamed the San Antonio Portland Cement Co., moved to its new quarters known as Cementville on what is now the site of the Alamo Quarry Market. After that, the city-owned tract became a city quarry that supplied crushed rock for street building, a trash dump and a materials yard (storage space for construction materials).

Refugio Lopez probably didn’t stay with the cement company. Most documents list his occupation as “carpenter,” including the 1910, 1920 and 1930 U.S. census and city directories between 1908 and 1929. Earlier than that, the directories list him as a gardener or laborer.

He may have come back later to the old quarry to work on one of the many civic-minded projects that made use of its strengths — natural beauty and essentially free rock. As the cement company said in a 50th anniversary advertisement in the San Antonio Express, Jan. 29, 1930, “in all the world, there is not another abandoned manufacturing site of comparable interest and charm,” citing “Brackenridge Park, with its unique Sunken Garden and Japanese Lily Ponds (now the Japanese Tea Garden)” and the “section of the old quarry which the city of San Antonio now uses to house the cages of its zoological exhibit.”

The idea to make San Antonio “the South’s first cageless zoo” came from a group of residents who formed the Zoological Society of San Antonio, a support group whose members would “contribute toward the purchase of new species,” said the Express, Dec. 30, 1928, and would continue to “take an active interest in (the zoo’s) growth.”

The St. Louis Zoo provided an example — “barless” enclosures whose construction “in natural depressions” allowed animals to move around freely in more natural-seeming surroundings while separated from human onlookers by smooth walls, moats and elevated walkways for viewing.

The result was “more humane treatment for animals” with “plenty of room for exercise (and) natural sunlight.”

Besides being more enjoyable for visitors, this form of display was cost-effective. Under better conditions, fewer animals would die and need to be replaced, and “surplus animals” could be sold for “a source of considerable revenue.”

ZOO HISTORY: San Antonio’s first zoo not moved but scrapped and sold

At this time, the zoo was owned by the city, which approved the modifications for the bear and monkey exhibits. Carlton Adams of the firm of Adams and Adams was the architect, and W.C. Thrailkill was the contractor for the improvements, which were formally presented to the city by the Zoological Society board in November 1929.

A bear pit, in three sections for different species, was built in a section of the old rock quarry adjoining the zoo. Nearby was Monkey Island, “where hundreds of monkeys of all varieties cavort unhampered by cages,” said the San Antonio Light, Nov. 3, 1929.

Judging from the model of the Thew Automatic Shovel (steam shovel) and the background, the photograph you shared of your grandfather at work in front of a rocky construction site was taken during the 1920s, maybe at the Monkey Island construction site.

“The limestone cliffs in the background of the bear pits were a lot higher than the ones shown in this photo,” said Lewis Fisher, author of “Brackenridge: San Antonio’s Acclaimed Urban Park.” By the time this photo was taken, he suggested, “the crew could have moved on to Monkey Island, with its lower rock outcroppings.”

MORE PARK HISTORY: Brackenridge Park’s Mexican Village catered to San Antonio tourists for 20 years

The “barless” exhibits were so successful that the city announced plans to “replace cages holding the smaller animals with pits similar to the bear pits” and for “a pit for the elephant in an old rock quarry behind Monkey Island,” says the Light, Aug. 23, 1933.

“Some of these habitats are still in use and currently in the process of being reimagined,” zoo spokesman Cyle Perez said.

The classic rock settings currently are home to the zoo’s black bears, hyenas, spectacled bears, red ruffled lemurs and tigers. Black-and-white ruffled lemurs, camels and lions live in quarried habitats with the moats filled in, and the old Monkey Island was where the Africa Live Phase 2 exhibit is now.

“The zoo’s goal is to continue filling in moats and doing either mesh or glass fronts to the habitats to increase the animal’s space and bring guests closer to each species,” Perez said.

By the time Alamo Stadium was constructed for the San Antonio Independent School District in 1939 to 1940, Lopez would have been in his early 70s. In the 1940 census, his occupation is left blank, and on his 1941 death certificate, he’s said to be retired.

Alamo Stadium (mentioned here Feb. 14, 2015) was built with federal funds from the Works Progress Administration, which typically employed people who had been out of work and were found to be in need by a local relief organization.

After years of discussion, including proposals for other locations and protests by neighboring homeowners, the city conveyed 30 acres of quarry land to SAISD for $10 as stipulated by an ordinance passed May 31, 1939, with the WPA’s use-it-or-lose-it deadline looming.

Architects Phelps & DeWees & Simmons designed the district’s first stadium using the natural bowl of the old quarry. “The stadium will be built against the cliff wall on the west with the natural limestone forming a portion of the rim,” said the Light, Aug. 2, 1939, the date of the groundbreaking.

Limestone quarried on-site was used to complete the outer wall that enclosed the stadium. Additional parking was built in another part of the old quarry, and streets were extended to allow access.

The new facility was named “Alamo Stadium” by the SAISD school board, which had appointed a committee to sift through public submissions that included Bluebonnet, Bexar, Cactus, Laurel and San Antonio Stadium. The stadium opened Sept. 20, 1940.

The first printed reference to the nickname I could find was in a sports column in the Light, Sept. 23, 1940, by Harold Scherwitz that compliments city schools athletic director Claude Kellam on “your big rockpile.” From then on, most newspaper stories used some variation of this name, usually “the Big Rock Pile.”

“Alamo Stadium was built on the site of an abandoned quarry, primarily with brick, stone and cement,” SAISD spokeswoman Laura Short said. “As a result, San Antonio sportswriters started referring to Alamo Stadium with the nickname of ‘Rock Pile.’”

Topics: Texas, San Antonio